|

The Myth of ObjectivityToday we’re going to peer under the sagging back-office box springs, using our long-handled broom to poke around in the dust mice, the long-missing undergarments and disappeared socks, plus all that icky, formless crud that dares not speak its name, to summon a sadly neglected, little understood, one could even say thoroughly elusive artworld nebulosity, art criticism. Ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha hah! Okay, okay, okay, you caught us, being exactly what our many frothing Rotund detractors say we are: sarcastic, disrespectful, unpleasant. Go ahead, go ahead, stop sending the big checks, stop offering the choice paintings, don’t ever again hint at a long night of freaking, wild abandon. See if we care. Why are we unearthing this particular stinking carcass once again? Well, we awakened this morning to the sound of Sunday’s El Nuevo Día thudding against our front door like heavy pudding and on opening the thing up, what to our groggy but wondering eyes did appear but three separate—though, as you’ll read, not equal—features about visual art. This, we suppose, is a happy development given the paper’s recent history of glossing over the cultural hubbub that’s been building like crazy for the past couple of years. So-called alternative spaces, CIRCA, the endless DIY shows, the whole simmering pot of habichuelas. This sudden plenty of arts writing at El Nuevo Día, along with the expanding coverage of art in some of the island’s other daily newspapers—as noted by Javier Martínez in his culture blog Autogiro, here—makes it seem like the effervescence of the local art scene is finally leaking out into the real world, where our dear, habitually underinformed friend General Public can learn a thing or two about it. We say hats off to the local press, especially the powers-that-be at the island’s largest daily, El Nuevo Día, for finally getting a clue. Many of our pals have thrown up their hands in the face of the paper’s apparent intransigence and insist that the future of serious arts journalism lies with the internet. But we’ve long been of the opinion that Puerto Rico’s growing, impetuous—and, not coincidentally, increasingly spectacle-like—contemporary art scene is newsworthy, in the way that any homegrown niche enterprise becomes news as it lurches nearer the hideous embrace of the global economy. We happen to think that our particular artistic moment has the added value of showing some pop culture fizz while maintaining at least a smattering of its traditional, high culture cachet. It’s a story that doesn’t need arcane analysis—not from the likes of El Nuevo Día, at any rate—just some clear, well written exposition; good reading with a proper soupçon of gravitas. The all-too-occasional pieces by Mercedes Trelles in the Sunday magazine at El Nuevo Día fulfill perfectly the needs of the art scene to have its story told while giving everyone else an edifying glimpse of what’s gone on behind studio doors. This week, Trelles serves up a perfect example, an appraisal of Garvin Sierra’s Que Díos te lo pague, the exhibition of print-based works, many in 3D, now on at el Antiguo Arsenal de la Marina Española. The review is textured and clear, an articulate, honest reading of work that is admirably experimental but not always up to its ambitions. Would it seem picayune and ungracious of us to point out that otherwise, especially in its recent, dismayingly awful writing about so-called “alternative” venues, El Nuevo Día continues to traffic in forgettable dross when it comes to talking about visual art? Of course it would. We are notorious quibblers and our fame for flogging dead horses goes way back, to the championship days of ‘67. Well, tormented friends, we’re going to ask you to bear with us through just one more ponderous, text-heavy rumination—completely unrelieved by catty-wampus, out-of-focus, garishly colored images—in which we snorffle about the problem of what etiologists, ontologists, endocrinologists, astrologers, proctologists, alchemists, plumbers, ornithologists, and other deep thinkers call “root causes.” For this weighty inquiry, we all have to put on our thinking caps—you know the ones, the propellered beanies that say “I’m With Stupid”—and clamber once again into our Wayback Machine for a trip to May 26, 2007, the date that El Nuevo Día editor Mario Alegre Barrios wrote in his official blog about “that pompous rhetoric so common in an infinite number of critics who usually seem to write only for themselves or their friends, who then flatter the critic and say in the most syrupy, servile tones, ‘Hail to the maestro. How much you know about art!’” Really. He did. But we’re getting ahead of ourselves already, and usually we’re so far behind. “Not fair! Out of context!” you might well cry, and go ahead. You’re absolutely right. It’s even worse than you think. We’re about to translate some excerpts from “Criticism: Easy-to-Build,” the title of that day’s post, and do a certain amount of paraphrasing. Alegre Barrios has accused us more than once of not understanding the “subtleties” of his writing in Spanish. You can judge our acuity and fairness for yourself by visiting the paper’s website, following the menu bar to “Blogs” and thence to “Flash” on the drop-down menu. The entries are dated in descending order, with the most recent first. But why pick on the poor man, who has shown himself to be much too thin-skinned for so public a figure? In fact, we admire his bravery for sticking his snoot out there in the first place. And giving the one-two punch to people who are no friends of ours. The fact is that, in this May 26 post Alegre Barrios lays out what he claims is the paper’s reasoning for not hiring a bona fide art critic. Apparently the paper has nothing in print in this regard so we have only the blog to go by, a shaky vessel of policy for sure. Let’s be fair for a moment and put that quote above in context. Weird shtick aside, Alegre Barrios is not unreasonably comparing what he believes to be the unfortunate habits among the island’s arts writers to what the paper expects from its employees: first of all that you have to know something about art, and secondly that you can write about it clearly and well. In his view, local writers write merely to enhance their own reputations among friends while the paper’s responsibility is to help its broad-based reading public form educated opinions about artists and the work they do. “Building bridges,” he calls it. However much it diverges from the reality, we have no problem with this assessment of the paper’s aspirations, and Alegre Barrios may be right about the egregious failings of writers here prior to the time we arrived two years ago. We see no shortage of serious, informed, talented commentators on the scene right now: Trelles, Pedro Vélez, Javier Martínez, Marina Reyes, to name a handful. The much graver shortcomings in the editor’s argument—and therefore, presumably, in El Nuevo Día policy—involve what an art critic in this day and age is supposed to be up to, and not be up to. In addition to their expertise and writerly chops, Alegre Barrios says, the paper’s employees have to “pass the test of objectivity so necessary for the job, without any conflicts of interest, real or apparent. “The majority of those who flaunt the title ‘art critic,’” he writes, “have close ties to galleries, museums, and artists, relationships they often use to write catalogue essays for exhibitions by those artists. Usually these texts are full of praises and grandiloquent adjectives . . . The essays are commissioned precisely for that reason, and for that [the critics] receive some kind of compensation. The problem begins when these same critics try to write an ‘objective’ critique of the exhibitions for the paper. These aspects are not negotiable in any way for El Nuevo Día . . . ” If all of this accurately reflects the newspaper’s thinking, El Nuevo Día is stuck up to its sagging buttcheeks in an imagined art critical past. The idea that there is some kind of “objectivity” possible in today’s artworld imbroglio is, of course, a throwback to the thinking of a half-century ago and laughably out of touch. And as professional writers, it’s hard not to feel insulted by the notion that catalogue essays get written only because the writer has “close ties to galleries, museums, and artists,” and that the writing, therefore, is hackwork. In our experience, writing a catalogue essay provides a unique opportunity which, in crucial ways, is entirely unlike writing criticism. It is first a chance to consider the entire trajectory of an artist’s career rather than focusing on the particular moment of an exhibition. It’s an appropriate occasion to write lyrically and at length, while criticism requires considerably clunkier moves: comparing this show’s work with last show’s, Sam the Sham’s with Hirty Girty’s. It’s almost a formula, redeemed only by the opportunity to make bad artworld jokes. And of course with reviews, there are those pesky, increasingly minuscule wordcounts. Doesn’t the catalogue essay writer’s talent and experience count the same way that an artist’s does when creating a public commission, and merit the same scale of pay? The sort of distinctions which Alegre Barrios makes in “Criticism: Easy-to-Build,” besides being fallacious and antediluvian, force writers into untenable choices. No newspaper—no magazine for that matter—is going to pay more than a pittance for reviews, although any writer with the remotest sense of serving the community is more than happy to do them. Why not jettison the outmoded criteria for writers which Alegre Barrios describes in favor of something in keeping with the times; an approach based, say, on originality rather than the myth of “objectivity”? If you write catalogue texts, you must write for the paper from a different perspective. This is sensible in today’s multifarious climate and easily verifiable. In the realm of journalism, it seems a far more essential ingredient to good work. Most importantly, it permits a writer to undertake both serious criticism and a freer, perhaps more poetic but no less honest type of writing—as long as the writer’s being honest—which catalogue essays allow and for which the writer gets appropriate remuneration. On a different but related note, Alegre Barrios concludes his post by noting that the paper’s criteria for writers—that they be knowledgeable, capable, and free of conflicts of interest—“far from being capricious, are rooted in common sense.” El Nuevo Día can define “conflict of interest” any way it wants. You cannot accept gifts from the people you write about. You should not ask for favors of any kind. You do not write about people you are related to by family ties. No art-institution munchkins allowed. Hiring out as an appraiser is frowned upon. These are common concerns of publications everywhere. Even the paper’s insistence that a writer who writes a catalogue essay on a particular artist cannot undertake a critical analysis of that artist in its pages is entirely its prerogative, no matter how myopic it appears to the rest of us. But if El Nuevo Día hopes to be known as an institution whose policies are anchored in something more than common sense—that is, in fairness—it had better write them down, so as not to mistake the selection process as an arbitrary one. Where Do We Go from Here?We promised reviews, we promised juicy descriptions, we promised all kinds of things. Instead, we’ll do something else, something hip and modern-day. We’ll show you some links to the websites where people have actually been doing their jobs. As we mentioned before, Javier Martínez has become a stalwart and vigilant commentator whose culture blog Autogiro is a must-read for the au courant. Martínez gives us the lowdown on Garvin Sierra’s exhibition Que Dios te lo pague at el Arsenal de la Marina en la Puntilla, in addition to a little outburst from the public that never quite ignited a scandal. Read about the exhibition here and the non-controversy here. For a detailed review of the show, try to pick up the Sunday, June 17 El Nuevo Día and peruse Mercedes Trelles’s latest contribution to the paper’s magazine. Martínez also mentions the just-opened exhibition by Karlo Ibarra at La Casa del Arte in Puerto Nuevo here. But for good shots of the opening-night crowd and the works in the show, we recommend you go toot sweet to Repuesto, the artblog project of worthies W&N. Ibarra’s exhibition is on view here, and there are also links to a short-lived but very good-looking show at Galería Raices—with Carlos Ruíz Valarino, Alejandro Quinteros, and Carola Cintrón Moscoso—here. The more you root around at Repuesto, the curiouser it gets. Ibarra’s exhibition continues until July 29 at the La Casa del Arte, Avenida Andalucía #500. Call Guillermo Rodríguez at 787-792-7373 for further details. W&N will themselves be in the BLOG show at Casa Candela, opening Thursday night, June 21 at 7 pm. The revolú is upstairs at 110 Calle San Sebastián in Viejo San Juan. Be there or be you-know-what.

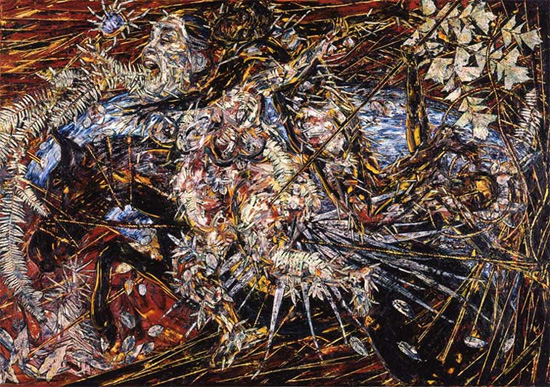

Our too-too friends will probably kill us for saying so, or at least hoot us out of the building the next time we meet, but we very much enjoyed the long-running, way, way overstuffed exhibition El Caballo en la Cultura Puertorriqueña, late at La Ballaja. El caballo show, as it was popularly called, was basically a vanity project, initiated by someone with a passion for the subject and the means to put it all together. Jannette Figueroa was the person, and she hired a curator, Adlín Ríos Rigau, to see the project through. We published a literary magazine for more years than Rip Van Winkle slept, and in all that time “vanity project” was a less-than-polite term for other people’s doings. In this case, the origins of the show did not reflect badly on the result at all. At its best the exhibition was an anthology of good and great hits from the history of Puerto Rican art. Sometimes it looked as though a hint of an equine presence in the work was a mere pretext for its inclusion, and whole sections of the exhibition seemed to be about something else: the jíbaro in Puerto Rican art, for example, or the romantic landscape. The image above shows a mural-size print by José R. Alisea, Los Perros (Homenaje a Don Luis Díaz Alfaro), 2001. It’s described as a print on cast paper, owned by el Instituto de la Cultura Puertorriqueña, and apparently it was never hung before this exhibition. Below, we present a highly random sampling of other things we liked; including, first, a small print by José Rosa, La bestia herida, 1984, which reminded us of José Clemente Orozco’s ferocious easel paintings of conquest-era battle scenes, on view at Museo Carrillo Gil in Mexico City. Below that, Arnaldo Roche Rabel’s Huracán del sur, 1991, and, finally, a work titled Pica de Personajes, whose author we’re guessing is Julio (Yuyo) Ruíz.

Not included is an image of our fave: Ramon Frade’s tiny landscape with washerwomen, Lavandería en el río, c. 1940-45. If you know where to find it, hunt out the March-April 2007 edition of the magazine DIÁLOGO-Zona Cultural, in which Manuel Álvarez Lezama writes about the exhibition. Will we see you again soon? We hope so. Meanwhile, zip into the recent past below. Art criticism, that’s all people talk about. See why here. |