The Instituto de Cultura Puertorriqueña (ICP) has had its ups and its notorious downs just in the year that I’ve lived in Puerto Rico, but the newly revamped visual arts section has a dedicated, talented crew, and knowing their stuff, they’ve enlisted the Rotund publicity machine to pass along some news. Read the announcement regarding an important, and rewarding, graphics competition at the 2006 edition of the International Print Biennial in Liège, Belgium, by clicking here.

For sanjuaneros—or anyone from anywhere on the island, for that matter—a visit to Espacio 1414 on Fernández Juncos is a chance to experience a little of the often slight but sometimes rousing drama of contemporary art. The ascendance of the contemporary scene is a truly global phenomenon that we isleños are surprisingly and sadly innocent of. Espacio 1414 provides an easy-to-swallow antidote for that ignorance. It’s the congenial showplace of art collectors Diana and Manolo Berezdivin, who have been buying the new and the newly classic all over the world for the past thirty years. They have a curator, the knowledgeable, diligent Julieta González, who mounts thematic expositions for the public from among the works the couple have bought.

One day we’ll poke around the Berezdivin collection and its home at length. It’s a good story, and our conversations with Diana have always been fun. But for now, just before the Rotund presses are given a much-needed rest from their informative yet cantankerous strum und drang, we’d like to point out that Espacio 1414 is filled with light-based works and looks more sprightly than ever. Sprightliness may not always be what you want from your art, but in this case González’ selection should enliven even the haughtiest, most perpetually dismayed snoot.

For those who absolutely require a little brow furrowing with their pleasure, the curator has this to say, roughly anglicized by the Rotund translation program, Babelcheese, about what’s there: “Many of the works go beyond optics and appeal to the body’s experience in the space, mediated by the light. Other works bring to this experience a reference to meanings that transcend the spatial and enter the realm of ideas.” Fair enough.

The first thing you might notice if you’ve visited Espacio 1414 in recent months is the airiness of the installation, which is, nonetheless, impactante in a way that González’ recent painting shows took some time and effort to comprehend. “La luz en el arte contemporáneo a partir de una selección de la colección Berezdivin” (Light in Contemporary Art As Seen in a Selection from the Berezdivin Collection) is an instant immersion in what’s before you, because it is, to use a little Beatles-speak, all around. There is very little in the show that you simply look at—the first thing inside the door, Jim Hodge’s painting-inspired “There,” 1999, is such a work—and a great deal in which, as González implies, the form or image of the work is just the vessel of an optical or otherwise sensory thrill.

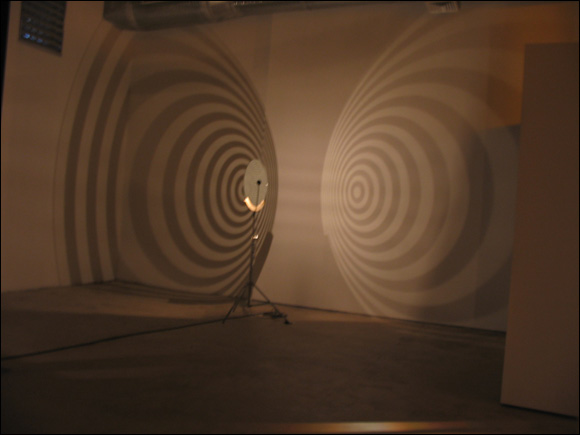

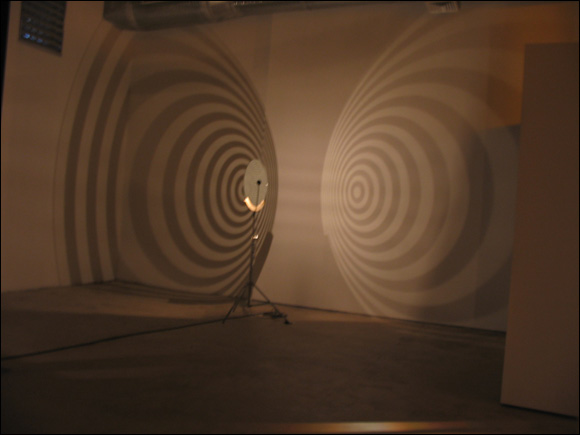

The hardware is very cool. Look at a camera-flash-flattened photo of Olafur Eliasson’s light- and-shadow device, “Shadow Lamp,” 2005, on the left, and tell me you’re not impressed.

But it’s what’s on the walls, and in the air itself, that might put you in a mind of those psychedelic light shows you used to enjoy the Electric Prunes and Quicksilver by, and you might even get a little giddy thinking of those great, far-out times. Even if you’re not sufficiently codgerly to be so swept away, the effect is probably much the same, a swoon of the kind offered by a crystalline, starry night sky.

On the second floor, the standout is a series of effervescing pods by the team of Consuelo Castañeda and Quisqueya Henríquez, called “sin título,” from 1996. In their explanation of the work, the artists invoke enough heavyweight art-critical bombast to satisfy the most hardened post-structuralist, but all you really need is a remnant of pre-pubescent wonder to love it.

While you’re awaiting the full effect of Castañeda-Henríquez’ timed illumination bursts, you might sidle up to the nearby shelf-load of paper lamps, “You Can Build Your Own City at Your Own Risk,” one of Carlos Garaicoa’s inquiries into the nature of soul-level urban decay, from 2001. Once Garaicoa built an entire model city out of candles and burned it down, and while the Berezdivin’s work is not this spectacularly ephemeral, it is a marvel of contained evanescence and shows the same tomb-raider’s curiosity and aplomb.

I dare say there is nothing not to like in this show. Even Allora and Calzadilla’s relatively featherweight empty-room light game, “Traffic Patterns,” 2001-2003, gives off a candy-cane glow in the vicinity of so much jolly combustion.

Espacio 1414 is readily accessible to the public with a phonecall to Ms. González at 787-725- 3899 or 787-235-2663. The collection is located at Fernández Juncos #1414 in Santurce.

The image at the top of the page is a shot of Olafur Eliasson’s “Shadow Projection Lamp,” from 2004.

Speaking of the contemporary scene and its presence on the island, Anthony Goicolea, a young man with one of the most inventive, baroque imaginations operating today, recently came to Museo de Arte de Puerto Rico for the opening of his new installation in the museum’s project room; four videos under the collective title, “Actos compulsivos.” We’re seeing this very important work thanks to the efforts of recently departed curator, Marysol Nieves, who, fortunately for us, still has projects pending to complete her commitments to the museum.

Goicolea, who just won the Patricia and Phillip Frost Art Museum’s prestigious Cintas Foundation Fellowship, along with Miami-based Glexis Novoa, has achieved a remarkable level of recognition among young contemporary artists. You rarely visit a meaningful group exhibition or a collection of any consequence without coming across his work. He is best known for photo-collages of astonishing technical skill and profound disquiet; tableaux in which the artist himself, in the guise of a crowd of young mop-topped boys, usually in shorts and knee socks, is doing things—or seems about to do things—of ordinary but pronounced nastiness. One gloriously lengthy montage shows a group of boy Anthonys idling about while waiting to look into the underpants of a young girl, also the artist.

For our delectation, Goicolea has brought a range of craft and disgust that is almost unwatchable on the high end: a young fellow abed with the glowing eyes of a zombie demon, chewing his nails while he should be sleeping. The scene, from “Nail Biter,” 2002, features a lot of drooling and excruciating moments of cautious listening—there is, even in his least disturbing tableaux, an element of wary anticipation which I read as the thrill of possible detection—and it almost outdoes, in two minutes and forty-four seconds, the entire feature-length psychological hectoring of David Lynch’s classic, “Eraserhead.”

Goicolea’s other works here do not lean on you as heavily, and, in my judgment, neither do they show the sure hand of the artist’s photographs. But the way they portray to extremity the horsy nervousness at the heart of youth’s most horsy years—via hair pulling, blackboard scratching, and falling down stairs with the heebie-jeebies—places him in the same investigative realm as Carlos Garaicoa. Goicolea’s approach is more surgical while Garaicoa’s tends toward the poetic, but they both seek to open up the human spirit with the incisive instruments of their artistic powers.

An impertinent question about this exhibition, or rather about the museum’s reception of it: I spent a lot of time at the opening, and although Marysol Nieves was graciously present throughout the evening, I didn’t see the museum’s director or any board members I know. Is it possible that these worthies did not bother to show up for an opening of this magnitude? Maybe I missed something, but if they didn’t attend I see little hope for the institution’s immediate future as a relevant contributor to Puerto Rico’s cultural life. It would be a clumsy pratfall, but not entirely out of character considering MAPR’s recent moves.

Goicolea’s installation, “Actos compulsivos,” will remain at the museum until October 22. The museum’s address is Avenida De Diego #299. It’s open Tuesday to Saturday from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m., except for Wednesday when the doors stay open until 8 p.m. On Sunday, the hours are 11 to 6. Admission is $6 for adults and $3 for children, students, and what they used to call “senior citizens.” For guided tours, contact the museum's education department at 787-977-6277, ext. 2230 or 2261.

A bloody, eviscerated Frida Kahlo corpse that stands for the death of painting? A good five, perhaps seven long minutes of a grandstand full of individuals flipping the bird, shouting foul imprecations, ululating, banging gongs, crying, and otherwise exercised at what is surely a wrestling match? Yes folks, you may have seen ideas like these before. In fact, some may have occurred to you, yourself—Heh, heh. Naw—before you wisely forgot about them.

But the Exposición de Graduos de la Escuela de Artes Plásticas should be a must-see for anyone who is interested in what might be lurking around the corner for the contemporary art world of San Juan, and this year’s edition has more than enough elán, frescura, and even a measure of proficiency to make the trip to the Cuartel Ballajá in Viejo San Juan very worthwhile.

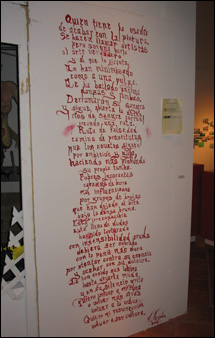

As it is throughout the contemporary art world, installation rules at the Ballajá, along with a good helping of video. Painting is not absent, but its presence is considerably reduced, and what’s there is not the best work in the show. That might, indeed, be Mario Arcadia Panet’s eerie diorama, “¿Quién mató la pintura?” featuring not only Frida with guts hanging, but also a stick with a wig—who else but Andy Warhol?—a cockroach-infested chess board, and a faux bitter manifesto written in faux blood. A better title might be, “¿Quién sobremató la instalación?” Good going, Mario. What else can you do?

On the beauty side, there is the silky, womb-like hive at the entrance to the show, “sin título,” by Joenally González Rivera. The opulent folds in all shades of pink and apricot and the varying degrees of softness seem to be the point, and the work must be wriggled inside of and touched copiously to really be appreciated. Brazilian sensualist avant gardists and their wearable art come to mind, as does the redoubtable Ernesto Neto, minus the spices.

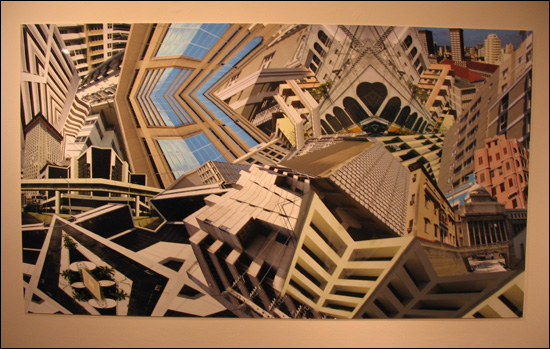

We’ve all seen digitally diced, sliced, bent, and folded imagery made to look like things we ought to recognize but don’t quite: jet-liner wings over ocean vastnesses paired to resemble alien craft from deep space and so forth; usually silly, snoozy stuff once you get the obvious point. But Luis Pérez Rivera is a Photoshop master with ideas about the kaleidoscopic queasiness of the urban landscape, and its loopy beauties in spite of all that. “Ciudad y puente” is a standout, reminding me, for some reason, of the semi-abstract, sky to Earth paintings of Franz Akerman. (You can see Akerman’s work at Espacio 1414 when it’s trotted out for a painting show, and you should.)

Unpromising beginning worth sitting through: Jason Mena Martínez’ drainpipe meditation, “Drip-drop-di-drap-di-drep,” turns out to be far more interesting than its name, owing to a cool soundtrack that creeps up on you and pounces. Who knew that plumbing could be so orchestral?

One of my personal favorites, due to the presence of flamboyán blossoms, is Genaro Ozuna’s “Altar fundamental,” which, by way of the dying flowers, plus black beans, lentils, coconut palm seeds, and several other fruits of the earth, forms a mandala of sorts. According to the artist, however, it is not really a mandala but his own concatenation of many spiritual strands, including Ghanian adinkra. The various grains, pods, and husks are outlined with a tracing of cornmeal that ends in vodu bebes at the cardinal points, and a bent, seudey column juts from the center of things, looking somewhat like the stamen of a monstrous deep-jungle flower that blossoms once a decade. If you are lucky, Ozuna will be there watering his art work. Seriously. He hopes the beans will turn white, the cocoa palm seeds red, the blossoms brown . . . you see how it works.

Inexplicably, this show does not last long. It’s up until June 30 in salas 2, 3, y 5, segundo piso, of Museo de las Américas, Cuartel Ballajá. Their several years out-of-date web site says that weekday hours are 10 to 4, Saturdays 11 to 5, and you may actually talk to a human being if you call 787-729-0007. Don’t blame Rotund World for a número equivocado.

Images from top: The Rotund Credits Police found out this video is titled “sin título,” by Daniel García Soto. Next: Mario Arcadia Panet, “¿Quién mató la pintura?” 2006, installation (with detail at right), dimensions variable. Joenally González Rivera, “sin título,“ 2006, installation, dimensions variable. Luis Pérez Rivera, “Ciudad y puente,” 2006, digital photograph, 40" x 120". Jason Mena Martínez, “Drip- drop-di-drap-di-drep,” 2006, digital video, time unavailable. Genaro Ozuna, “Altar Fundamental,” 2006, installation, dimensions variable. Forgive us: we can’t vouch for color accuracy.

What are you doing down here? Perhaps you want to know more about the legendary Rotund Chickamunga Irregulars and their crack unit, the Walking Crabwise Big Dawgs. Who can blame you? More about that when we return from our Rotund snooze.

If you missed our last episode, a consideration of the good, the bad, and the sleepy in arte graffiti at Galerías Prinardi, cliquea aquí. Still hungry for all things CIRCA? Gluttons for punishment can revisit Rotund’s snarkfest here or just wait. There is plenty more where that came from.

Think the Muestra Nacional is too derriere garde and criollo for the likes of you? Coño, think again. This year’s edition will be más caliente than a pistola que cuesta dos pesos, as George “El Jíbaro” Jones puts it. If you’re an artist who has resided in Puerto Rico for at least the past three years, read the prospectus above and then shake their tree. Please. Although the document doesn’t mention it, if you live elsewhere but have family connections with la isla, you may also be eligible. En cualquier caso, no ganas si no juegas.