Something has been bugging me ever since I wrote about Pedro Vélez’ exhibition, “Godfuck,” at the very schnoz-worthy Galería Comercial. No matter what I said before, this is the sign of a very good show, so I’ve decided to revisit it here in Rotundolandia in spite of all else that’s going on and the ridiculously laggardly pace I’ve established in covering it.

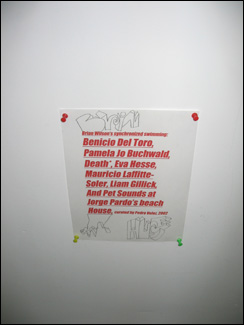

quite the sport about it. You hire a band. At the opening, you schmooze and yell and drink yourself stupid and people fall down. Sincere but out-of-it interested parties, including an actual museum curator, stop by the gallery one day, asking a lot of perky questions and delivering vague and largely false encomiums about a show they don’t get but think they should. You complain to them that nothing’s sold. Perfect. There’s an artist, a dealer, a curator, and no sales. It’s almost an art show. What it lacks is a review, and voilà, the cranky old pundit at Rotund World delivers. It’s official. It’s art.

I realized that I hadn’t quite gotten the idea when I visited the studio of the aforementioned good-sport painter, Jorge Zeno, and he mentioned that he and Pedro go back a few years and he’s participated before in Vélez’ fake art shows. Well, that’s god-fucking it, I thought. Another in a long line.

Wall, above left: JFPT (Slobodan Milosevic), 2006, collage left: HUSE, 2006, above: installation shot with banners and collages.

But Vélez is much too smart and works far too hard for there to be nothing at all going on here in altered-found-object territory except a lot of irony and attempted hoodwinking, even if the point’s a pretty good one. I had started to drift toward this point-of-view even before my conversation with Zeno. At some point Vélez’ show put me in a mind of the ingenious, perfectly ambiguous concoctions of silicone slather, digitally altered pornography and war imagery, chunks of Stryofoam, and hefty turnbuckle-and-cable armatures that Fabian Marcaccio fabricates, his so-called “paintants.” At Comercial, Vélez has created an ambiance that, from a certain angle, looks and feels a lot like the urban – or, on another level, consumer – landscape we inhabit. The tilted wall with posters near the front entrance reminded me more than anything of a giant cereal box. The banners dangling from the rafters fairly throb with overheated adolescent drama. The opening-night band, The Bukakees, supposedly had never played before (although this, cleverly, is in dispute). The bruised, pubescent girls in the posters are neither hurt nor particularly young. No teenagers were harmed for this art show! Like Marcaccio, Vélez puts a lot into his vacuity. It’s all exquisitely false and without value. Can you say the same about your favorite art works?

Manuel is my barber. First I tried Ivette. Right off the bat she nicked the tips of my ears with her clippers. Ouch. Damn! ¡Chica! Be careful! Then I visited a pair of old buzzards on Loiza, the neighborhood strip of bodegas, jewelers, fast-food joints, suspicious-looking restaurán-bares, pharmacies, and low-end tiendas de moda. ¡Perezosos! Mostly they couldn’t be bothered. There’s not much to do with the sparse Weinstein noodle, but them? Ni los ears ni los nose hairs. One day I wandered down a side street and there, through a storefront window, I saw two chairs and one, mostly idle, barber. At the time there was a crowd of youths in the small place, a promising sign, but it turned out to be the comings and goings of his children and grandchildren. Anyway, I walked in.

Manuel doesn’t have much to say. I’ve tried to draw him out. First I got a few dark mutterings about rising prices, the vultures and cat stranglers on the government payroll, and so forth, and I have to hand it to Manuel, you're going to be right just about all the time no matter how outlandish your vituperation and caviling when it comes to Puerto Rican politics. The island treasury is a succulent trough for its public servants. The scale and frequency of agency scandals are magnificent, more splendidly endemic than the hail-fellow-well-met corruption of Miami, more foully cavalier than the racial politics of Dallas. The public transportation system has a reputation for keeping whole fleets of perfectly functional buses stashed behind the bus barn – ¿Número 36? Lo siento mucho, no va a llegar hoy – gas and parts looted in vast quantities by anyone who asks, employees punching timecards for absent colleagues, and a boss who personally canceled the reservations of elderly and handicapped clients when they wanted to attend a hearing to protest a rate hike for the service they use, “Call & Ride.”

Well. What about the family, Manuel? He has a son who’s on the farm team for the Cincinnati Reds, and the baseball card that hangs between the mirrors says enough about that. Music? Does he likes salsa? Jeez, what Puerto Rican does not like salsa? That pretty much dried up the well, although he did take a minute to assure me that merengue, that quintessential Dominican music and dance, was actually invented right here in Puerto Rico, no matter what I’d heard.

But this unbarberly reserve of Manuel’s is all for the good. Because he has done for me what no other barber has ever done. I’ve been ministering to my beard myself for as long as I can remember, and when the barber says, “¿La barba?” I always demur. But one day, without prelude, Manuel took his clippers to the facial hair I’d already tidied up that morning, and before I could utter a “What the hay,” he was at me, cheeks, neck, and ears, with a straight-razor. It went on and on. After awhile, he was taking little dance-steps and clicking scissors to comb in time to the music on the radio. ¡Híjole! When he was done, after he slapped the stinging stinky stuff about my various wounds, I looked, and felt, like an entirely new fellow. A more debonair Joel than any I’d ever been, even the time I had to wear a tuxedo to some accursed actividad de gala for the art museum where my wife was working.

You can access Rotund World features and the archives here. This link takes you to the newest of the new and the freshest of the fresh. For last episode’s thrilling page one, click here. For something truly electrifying, and, I might add, edifying, click here. Meet two of the Three Kings and find out how you can sponsor and subscribe to Rotund World. For our first roundup of cool shows and cogent burblings about whatever, see this page. Curious about Booty Bundt? I would be too. Cuidao, mano. La tribu está salvaje.